What are we doing? In today’s confusing, demanding world, Catholic educators must frequently ask this question of themselves. Standards, tests, mandates, accreditation, programs, parents, students, board members, pull us this way and that all the time. But what is our goal? How can we steer a consistent path to that goal?

It is because of this that loyalty to the educational aims of the Catholic school demands constant self-criticism and return to basic principles, to the motives which inspire the Church’s involvement in education. [Sacred Congregation for Education, The Catholic School]

It is because of this that loyalty to the educational aims of the Catholic school demands constant self-criticism and return to basic principles, to the motives which inspire the Church’s involvement in education. [Sacred Congregation for Education, The Catholic School]

In today’s pluralistic society, Catholic schools have a unique goal – to pass on wisdom. Ideally, all schools share this aim, but the sad reality is that most have lost any vision of what makes human life really worth living. But Catholic schools have the great privilege and blessing of forming their students in the accumulated wisdom of the Church. The result will be truly free adults who can lead the best human life possible as they prepare for the divine life to come.

ASSIMILATION OF CULTURE

[A school is] a place of integral formation by means of a systematic and critical assimilation of culture. A school is, therefore, a privileged place in which, through a living encounter with a cultural inheritance, integral formation occurs. [The Catholic School, n.26]

The primary instrument of education and formation in a school is a culture. No one student or educator can sort through the diverse visions of the good, true and beautiful that assault us everywhere in the “marketplace of ideas” . This is where culture comes into the picture. A developed, lasting, impressive culture is one which has, in its various spokesmen, encountered the whole, diversified experience of human activities, and taken related positions on them. Culture provides a unified wisdom. The role of culture is so critical to education that recent Magisterial documents identify “cultural pluralism”, the idea that all cultures are of equal value, as the greatest challenge facing education today.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America shows how democracy is much more than a political system – it has been the dominant characteristic of Western culture since the 1700s. When a society becomes democratic, its views and tastes in religion, philosophy, art, science, math, history, language, education, all change together. They come to bear the democratic mark, the mark that says that all men are fundamentally equal.

As Catholics, we are blessed to be the inheritors of a rich, beautiful, rational yet mysterious, transcendent yet fully human culture that has developed over 2000 years. Our greatest task as Catholic educators is to form students who will be at home in that culture, who will draw on it throughout their lives, share it with others and enrich it with the blessings of contemporary life.

As education reaches a certain point of development, it opens up new and wider cultural horizons. It ceases to be a utilitarian parochial effort for the maintenance of a minimum standard of religious instruction and becomes the gateway to the wider kingdom of Catholic culture which has two thousand years of tradition behind it and is literally world-wide in its extent and scope. [Christopher Dawson, Crisis of Western Education]

Catholic culture, a great Providential blessing for the Church, is the rightful heritage of Catholic students. Catholic schools succeed in large part to the extent that they form students who are fully at home in this culture.

What are the marks of our Catholic culture? Let’s look at a few aspects, starting with our heroes.

Do your students know the story of St. Augustine and St. Monica, his mother? How about St. Benedict and the role the Benedictines played in forming Christian Europe from the remnants of great Rome and the barbarian hordes that destroyed it? St. Thomas Aquinas’s great labor to explain and defend the truths of the Catholic Faith? St. Philip Neri, the Apostle of Joy, and the other saints who renewed sanctity in the Church during the Catholic Counter-Reformation? Do they know St. Junipero Serra and the great work of bringing the Gospel to the Americas?

Stories of saints are an important part of the rightful heritage of Catholic youth. These are their spiritual fathers and mothers, of whom they can be rightly proud. In our secular times, only in Catholic homes and schools will they learn of them; as Catholic educators, we have the proud duty of passing their stories on to the next generation.

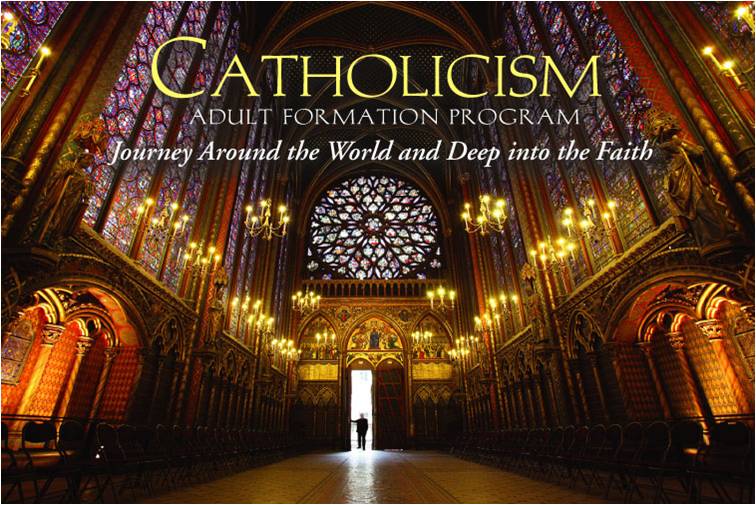

We need to tell our students the story of the Catholic Church as it has struggled and triumphed through 2000 years. Our students need to learn the great works of Catholic art, music and literature: Gothic cathedrals, Gregorian chant, medieval icons, Palestrina’s motets, Mozart’s symphonies and opera; Michelangelo, Raphael, DaVinci; Dante, Tolkien, O’Connor, Waugh.

Culture is more than just great works and deeds; “it covers the whole pattern of human life and thought in a living society.” Living in communion with the saints of the past is a great part of Catholic life, as is living in a communion of faith and prayer with the Church today. Catholic students learn to join their minds and hearts in prayer with the Church in the Holy Mass. They should learn traditional Catholic devotions such as the Rosary and the Stations of the Cross, and also come to know the Liturgy of the Hours, which forms such an important part of the Church’s praise of God.

Catholics have a way of thinking about things that sets us apart. We are a Church of mysteries that excite a sublime love and reverence, the most profound hope, the deepest yearnings. Yet we are also the Church of the Word of God, Who encourages us to use all the riches of human learning to delve into those mysteries and to share them with others. So the Church founded the great universities of Europe, and brought forth the works of Copernicus and Galileo. And the Church has from time to time corrected those who pretend to use reason and science to deny the mysteries that ennoble human life.

The Word of God “enlightens all men coming into the world.” So Catholics have always found it natural to find great good among non-Christians. St. Augustine taught the Church to think of pagan thought, literature, science, and history as gifts to her from Her Spouse. In a particular way, as Pope Benedict frequently stresses, the Greco-Roman civilization, in which Christ was born, possessed a devotion to reason, philosophy, ethics and law that self-consciously transcended the limitations of ethnicity and nationality. Although the Romans killed her Founder and persecuted her, the triumphant Church embraced the good that civilization contained. The work of St. Benedict ensured that it would be preserved, purified, sanctified. Following this example, Catholic schools pass on the true, the good, and the beautiful wherever it is found.

Our work as Catholic schools is a great and noble task, which is more crucial than ever in our day. Pope Benedict has made the preservation of Christian culture a top priority of his pontificate. As secular society increasingly turns its back on the Christian heritage that made it great, Catholic schools, walking in St. Benedict’s footsteps, play an increasingly crucial role in preserving this treasure for the world.

But the creation of this massive [Catholic] educational system [in America] is in itself a great achievement and may have an even greater importance for the future. For as education reaches a certain point of development, it opens up new and wider cultural horizons. It ceases to be a utilitarian parochial effort for the maintenance of a minimum standard of religious instruction and becomes the gateway to the wider kingdom of Catholic culture which has two thousand years of tradition behind it and is literally world-wide in its extent and scope.

[Originally published July 25, 2018]