Walking the streets of Old City Philadelphia last month was a thrilling experience for me. I have always loved history, and particularly the stories of the great men  and their deeds. American Revolutionary history was particularly fascinating because these were not foreign people like the great Romans or the even more foreign Egyptians and Babylonians. These were the founders of my country, a country that had a great deal of pride in its ideals and its heroes.

and their deeds. American Revolutionary history was particularly fascinating because these were not foreign people like the great Romans or the even more foreign Egyptians and Babylonians. These were the founders of my country, a country that had a great deal of pride in its ideals and its heroes.

Posted on one street corner was a reproduction of an 18th-century map of the city with prominent places labeled. “The Popish Chapel” immediately caught my eye: an opportunity to visit an important piece of Catholic history, and also a reminder of the great difficulties faced by Catholics in an intolerant Protestant country. As I shortly learned, the existence of the chapel, Old St. Joseph’s, was only tolerated because the concerned Provincial Council of Pennsylvania decided Pennsylvania’s Charter of Freedoms trumped the English Penal Laws forbidding Catholic public worship. Thank God for William Penn, the Quaker founder of Pennsylvania.[restrict]

Catholics were among the first to benefit from the developing sense of the importance of religious freedom in the New World. Fifty years later, President George Washington cemented American commitment to this principle by attending Holy Mass several times at Old St. Mary’s just around the corner.

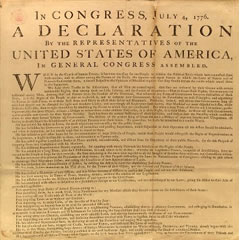

Stories like these have inspired and educated generations of Americans. America, with its population drawn from every part of Europe and the world, has been called a people united by a creed, a belief in the fundamental truths expressed in the Declaration of Independence. But it is also united by a shared pride in its history. Abraham Lincoln understood the deep importance of our history – we develop an affection for our form of government necessary to maintain our commitment to it. And so he hoped that the stories of the Revolution would be re-told in history “so long as the Bible shall be read.”

Americans have re-told those stories over the years, and new generations of immigrants have come to make American history their own. At our Thanksgiving Mass, our pastor, a second-generation Italian, referred with gratitude to “our founding fathers.” I never felt so strong a connection and deep a sense of gratitude as when, reading David McCullough’s John Adams, I read a letter which Adams wrote to his wife stating how all their suffering was worth it for the sake of the freedom they would win for millions of future Americans. Embracing the creed and embracing the history go hand in hand.

This valuable lesson should influence our teaching, not only of American history, but of Church history as well. The Catholic Church is universal, found among nearly all the peoples on earth. As one of my favorite hymns expresses it, “Elect from every nation, yet one o’er all the earth.” But differences of land and tongue and color and history naturally separate us. We need a strong sense of our own Catholic history to inspire and unite us. We need to hear the stories of the martyrs of the Church, the patriots of the New Jerusalem. We need to know of the great efforts of men like St. Athanasius and St. Augustine to protect and preserve the precious truths handed down by the Apostles, so that the title “Father of the Church” will mean something to us. We need to know how the Church transformed the barbarians who overran the Roman Empire, raising from many warring tribes a great civilization devoted, however imperfectly, to the worship of the one, true God. And we need to know the stories of men like St. Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul the Great, whose living faith shone so much the brighter the blacker were the atrocities being committed around them and upon them.

Christianity is an historical religion. This is not only true of the preparation for the birth of Christ. The history of the Church, whose beginning is recounted in the Acts of the Apostles and whose end is foreshadowed in the Book of Revelations, is the continued history of Jesus Christ, whose Spirit has developed His Body throughout time. Connecting our Catholic students with their past is the most important effect of history courses in Catholic schools.

[/restrict]